The many faces of concrete

VELDHOVEN - blog #2 Tuesday 19 May 2020

In this second blog, Gerard talks about the many faces of concrete.

A conversation during a chance meeting with a former classmate brings the following question;

“What are you doing nowadays – are you still in concrete?”

The idea that you can quickly get bored of something like concrete comes from the perpetual image that it is grey, monotonous and boring. But it is very easy to break through this idea: just put concrete die-hards in the spotlight and this mysterious material reads like a book that you can’t put down.

From the last century

In one of the cupboards in my office is a cardboard box containing concrete compositions from the 1960s and 1970s. Compositions that are written in ballpoint pen on a card so that whoever had to measure the raw materials could weigh out the right amounts. So that exactly the right amounts of concrete mortar were put into the mixer in order to fill a specific mould. Compositions that were a simple mixture of raw materials without whistles and bells. Concrete strengths that were described as a B37.5 and were calculated according to a Dutch Rengers Antonissen formula. The concrete was stiff and had a compaction rate of 1.20, so that earplugs were needed to withstand the sound waves from vibrator needles and tables.

It was used to construct large, complex residential towers in a style that can be described as abstract, but that was popular mainly because it was so efficient. They still stand today, just like the Chesterfield sofas that were so popular in the 1970s and have now become trendy again in these modern times. Back then, as it is now, it was not only about whether or not it was or is beautiful, but also possible and then you suddenly realise that concrete is timeless and can take on 1001 different shapes. And that’s the magic of it: concrete starts in a more or less fluid form that can be developed in such a way that it can be used again and again. The precast way of thinking in all its simplicity. The shape can be varied, but the material itself can also be made in all kinds of different ways.

The many faces of concrete

Concrete has many faces, but even more if you think about it working together with other materials. The primary combination with steel reinforcement means that it can withstand both compressive and tensile forces. Reinforcing steel that can be replaced with steel fibres or other kinds of fibres. The basic and coarse aggregates like gravel that are replaced by recycled concrete granulate. The most creative solutions are researched. Experimental concrete never stands still. Different materials working together with concrete demand the same attention as people who work together and are passionate about sharing their own materials from another core business.

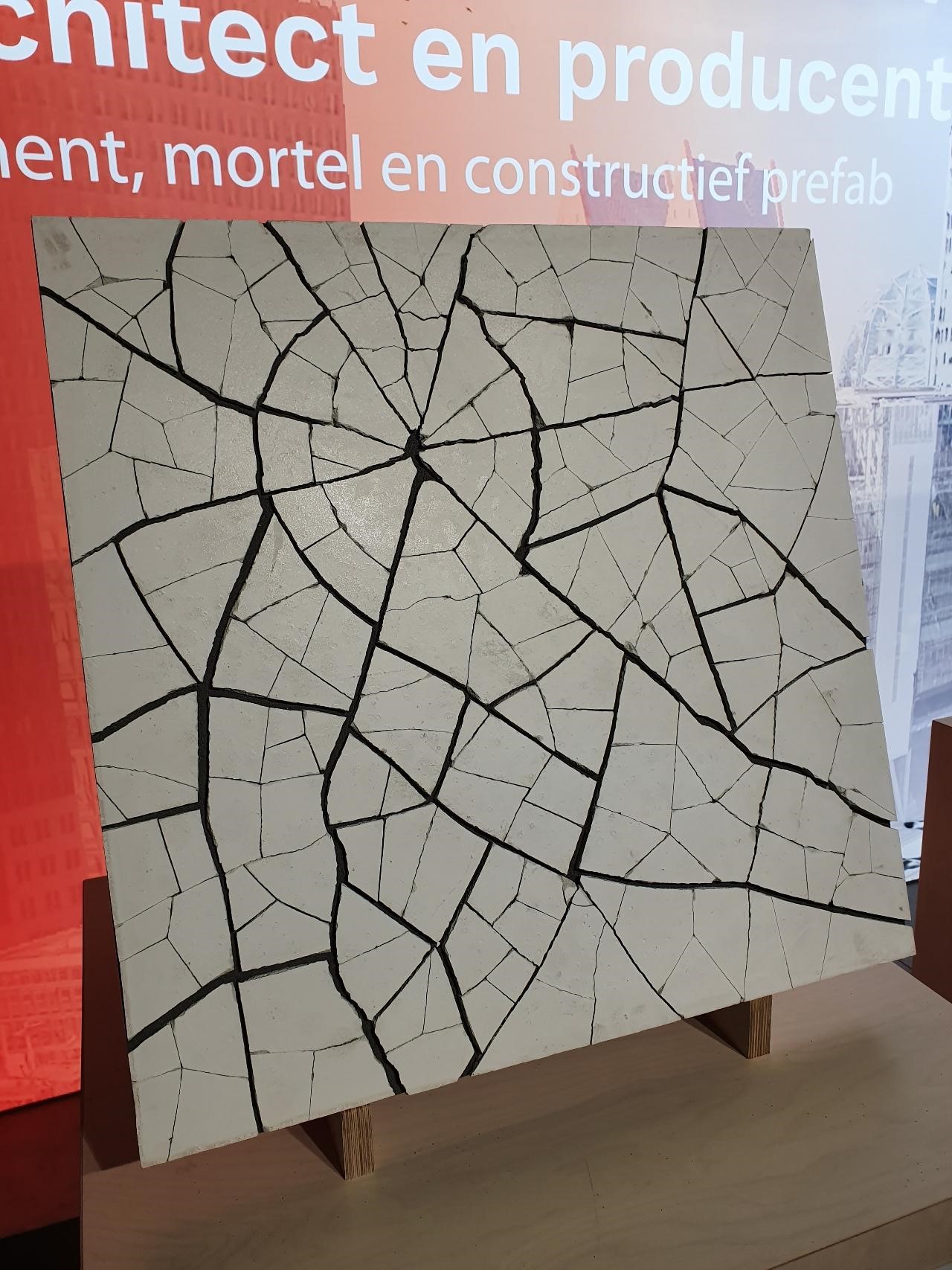

The idea of fixing something to the surface of the fresh, smooth, grey concrete is an option, but our laboratory is full of concrete samples that have been made with a basic principle in mind: whatever you add to the concrete composition can also be made visible. A beautiful word for concrete that remains visible is architectonic concrete. As usual, other names emerge over time, such as ornamental concrete. Concrete that can undergo further treatment such as blasting or polishing. These can also be divided into categories: dust blasting, deep blasting, sanding, gloss polishing etc.

Retro look

Nostalgia sometimes gets the better of me and then I retrieve a tile that simply consists of sand and gravel, and that has been washed out with a cement retarder on the floor of the mould; a coloured paste that is applied to the bottom of the casing like a layer of paint. The concrete mortar that is poured onto this is allowed to harden so that the element can be rinsed with water after removing the casing. This removes the surface skin of the concrete element that has not hardened and the aggregate that was added to the concrete becomes visible. Just like a washed-out gravel tile you sometimes still see in the front garden of a 1960s house. This retro look comes and goes in waves over the years. Washing out was suddenly back in 2010-2012. What’s great is that it is slightly different with the new compositions. The concrete was self-compacting: this means that no vibrating energy is needed to compact the material and remove the excess air, but that gravity is left to do this. The concrete was C50/60 with a flow size of 720 mm. You could sing along with the music on the radio because earplugs were no longer needed.

Self-compacting concrete is the magic word of the late 1990s. I can well remember that a Japanese concrete technologist took off his smart jacket in a factory in Brabant and rolled up his sleeves so that he could delve into the concrete mortar with his bare hands, right down to the bottom of the tub. The characteristic Japanese nod indicated his approval: a good, persistently stable mixture in which the deaeration was clearly visible because ‘it was bubbling like a pan of simmering pea soup’. Deaeration is essential for good compaction, but this does not mean that it is only good when all the air has been removed.

Two buckets of air

In a mixture we define the proportions of the raw materials. You want to create a stable and homogenous mixture that has the desired appearance after being treated. There are often discussions about the different aggregates and all the variations they make possible. However, there is one transparent component in the concrete composition that I would like to put in the spotlight once again. I have two plastic building buckets in the laboratory, each with a volume of ten litres. They stand there empty on the table, alongside various test samples. In order to demonstrate how much air can be present in one m³ after compaction, I point to these two buckets while explaining all about the possibilities of precast concrete. It is quite something to see how people look at these two empty buckets while I explain that they are not empty, but filled with air. I often calculate 2% air per m³ of concrete. 2% means 20 litres of air in every 1000 litres of concrete: exactly two ten litre plastic buckets full. Just consider that a very small proportion of this would be visible on the outside of your concrete element. You can make arrangements for situations such as air bubbles, in particular in vertical deposits. In fact, you must make agreements in advance. Of course, every concrete factory has its own ways of limiting the number of air bubbles on the surface, but I often notice that there is a kind of obsession about finding a few in the surface of the concrete. As if they then think ‘it is not properly compacted!’ The opposite is actually true. Realise that the strictest regulations recognise that there will always be air bubbles in concrete, and stay realistic.

Concrete has existed since Roman times and has constantly been redeveloped and evolved with a modern zeitgeist. It is no digital fantasy, but just the realistic, concrete truth. In my opinion, wonderful looking animations of projects, in which it apparently never rains, should be brought in line with the even more wonderful reality in which it thankfully does sometimes rain and in which air bubbles are visible in concrete surfaces.

Written by: Gerard Brood, Senior Quality Officer at Byldis Prefab

Special precast concrete elements for the Islamic Cultural Centre Lansingerland

Byldis with concrete elements trade fair GEVEL 2020: The possibilities of experimental concrete.

But wait... there's more!

In "Concrete chunks", Gerard Brood talks about his work as Senior Quality Officer and Concrete Technologist at Byldis. As well as a passion for his work, he also loves describing his observations. Want to read all the blogs? Go to: all concrete chunks.